Value-Based Reimbursement, Risk Adjustment & HCC Coding: What You Need to Know

Download this information as an eBook now!

Value-Based Reimbursement

Value-based care has emerged as an alternative to the traditional fee-for-service model; it is focused on quality rather than quantity. Depending on the healthcare organization, many teams are adopting population health and value-based care in addition to fee-for-service, making it increasingly common for both reimbursement models to coexist within an organization.

Value-Based vs. Fee-for-Service Reimbursement

In the traditional fee-for-service payment model that healthcare organizations have been using for decades, providers are paid for the volume and types of services performed. For example, each MRI performed, or unit of anesthesia delivered would be billed at a predetermined rate. As a result, providers had incentive to order more tests, perform more procedures, and take on more patients to receive more payment.

Value-based care ties payments to the quality of care provided, ultimately rewarding providers for administering effective care regimens and increasing efficiency. In more basic terms, value-based care models center on patient outcomes and how well healthcare providers can improve quality of care based on specific measures (e.g. reducing hospital readmissions and improving preventative care).

Why More Medical Organizations are Shifting to Value-Based Care

Although organizations are embracing the movement toward value-based care at various speeds, most are looking to implement value-based care models to combat rising healthcare costs and create a focus on preventative care. There are primarily three groups pushing for this shift for varying reasons:

- The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the largest single payer for healthcare, is projected to run out of money by 2026 at its current funding levels. As a result, Medicare is pushing for more value-based programs to reduce overall costs and improve quality for Medicare beneficiaries.

- Employers are pushing insurance companies to reduce the cost of providing healthcare coverage to their employees. Healthcare cost increases have been rising faster than employee wage increases for the last decade, and in many cases the higher healthcare premiums are consuming the dollars that would have gone to wage increases.

- Providers are embracing value-based care, allowing them to focus on providing the highest level of care.

Value-based care (also referred to as accountable care or population health management) is growing in popularity in part because the value-based reimbursement model provides incentives for providers to offer the best care at the lowest cost. As the name suggests, patients are receiving more value for their money.

Healthcare payers are also seeing significant cost savings after implementing value-based reimbursement programs. Humana reduced healthcare costs through Medicare Advantage Programs by $3.5 billion and Humana isn't alone. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina touts $153 million in savings in 2019, their first year of rolling out a value-based care plan. These examples show that, despite operating on different value-based reimbursement contract models, they could still see positive results following a transition to value-based care.

Value-Based Reimbursement: Contract Models

Because value-based reimbursement is based on the quality and cost of care, there are several models medical groups and insurance companies can use to align on payment. Three of the most common agreements include:

- Bundled Payments

- Capitation

- Risk-sharing

Bundled Payments: One Payment, Multiple Providers

Under bundled payments, a single, fixed payment covers all services associated with an episode of care. An episode of care could be a hip replacement or cardiac surgery, for example, and could include any inpatient, outpatient, and rehabilitation care costs. Insurance companies determine the fixed payment based on the historical performance of the hospital and providers.

In this model, healthcare providers receive rewards if they successfully generate additional savings and new efficiencies in care—such as better care coordination and less wasteful test ordering. If spending exceeds the predetermined bundle price, the healthcare providers will typically bear the financial risk.

The goal of a bundled payment is to get providers to work collaboratively to provide a higher quality of care while controlling costs.

Capitation: Medicare Advantage, Patient RAF Scores, HCC Codes & More

Capitation model arrangements pay a provider an advanced fixed fee—referred to as Per Member Per Month (PMPM).

The PMPM is often determined by the ranges of services provided, the number of patients involved, the relative wellness or sickness of the patient population, and the period of time during which the services are provided.

For example, Medicare Advantage uses a patient’s historical diagnosis history, which maps to Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) codes, to create a Risk Adjustment Factor (RAF) score. This score is then multiplied by the base PMPM capitated rate to determine the PMPM for the next period of coverage.

Because the capitation fee needs to cover the cost of care for people at many health levels, capitation creates an incentive for providers to control utilization and healthcare costs by avoiding unnecessary services.

Risk-sharing: Win or Lose Together

Under risk-sharing arrangements, both the insurer and the providers can share revenue if they deliver care at a cost less than the amount budgeted.

Some Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), such as the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), are structured this way, enabling the ACO to share savings with Medicare.

Risk-sharing arrangements can be set up so that providers or provider groups share in the potential profits or in the downside financial risk, if the cost of care exceeds the amount budgeted.

Risk Adjustment

Risk Adjustment in Healthcare: What Is It & Why Does It Matter?

Besides affecting the financial relationship between physician organizations and health insurers, risk adjustment also levels the playing field among health plans by allocating funds from plans with relatively low-risk (i.e., young, healthy) patients to plans with relatively high-risk (i.e., old, sick) patients.

CMS and commercial insurance companies use RAF scores to ensure healthcare organizations that cover sicker-than-average patients receive additional compensation to pay for the extra care and services they provide.

Calculating Patient RAF Score

As mentioned above, a risk adjustment score, or RAF score, acts as a predictive reimbursement model to estimate a healthcare organization's cost to care for a patient.

The primary driver of a RAF score is the patient's HCC codes, which represent specific medical conditions. The HCCs, together with the patient's demographic and program enrollment information (i.e., ACA plan, CMS dual eligible, ESRD, etc.) determine the patient's full RAF score; or their estimated cost to a healthcare organization.

See examples of RAF scores for two patients below. Joe Doe’s RAF score would result in a higher expected cost of care than Mary Jones's.

| Condition | Joe Doe, Age 85, Male | Mary Jones, Age 65, Female |

|---|---|---|

| Age-Gender Component | 0.686 | 0.323 |

| Specified Heart Arrhythmias | 0.268 | 0.268 |

| Cirrhosis of Liver | 0.363 | - |

| Morbid Obesity | - | 0.250 |

| Diabetes with Chronic Complications | - | 0.302 |

| Total RAF | 1.317 | 1.143 |

Medical groups that treat “sicker” patients, such as Joe Doe, incur additional time and effort in the care delivery process. This translates into an increased pool of funds (represented in PMPM payments in many cases), so they can effectively treat their sick patients.

For medical groups to ensure their “pool of funds” accurately reflects the wellness of their patient population, the accuracy and completeness of diagnosis/HCC risk adjustment coding is a must.

Benefits of Risk Adjustment

The benefits of risk adjustment are important both to insurance companies and providers.

Without risk adjustment, there would be an incentive for health insurers to only enroll lower-risk patients as a cost-saving measure. Risk adjustment mitigates that potential for discrimination and stabilizes payments to reflect differences in benefits and plan efficiency rather than the overall health of the population.

The intent of risk adjustment is to offset the cost of providing health insurance for individuals—such as those with chronic health conditions—who represent a high risk to insurers. Under risk adjustment, an insurer who enrolls a greater-than-average number of high-risk individuals receives compensation to make up for extra costs associated with those enrollees.

Since risk adjustment closely ties to reimbursement, providers also benefit from it. Risk adjustment enables more accurate reimbursement by accounting for differences in patient demographics and other risk factors that affect outcomes outside of the provider's control. Without risk adjustment, providers treating higher-risk patients would not receive payments that accurately reflect the relative health of the patients they treat and the quality of care they provide.

Physicians’ Role in Risk Adjustment

Risk adjustment relies on the diagnoses documented by the physician at the time of a patient’s visit. Physicians can (and should) focus on what they do best: providing excellent patient care. That being said, since risk adjustment models tie payments to outcomes, medical groups (and physicians indirectly) receive more appropriate reimbursement only when they correctly document and capture diagnosis codes.

For example, it’s not uncommon for patients to have complications related to a diabetic diagnosis. A physician who documents these complications as being affected by the diabetes will receive appropriate reimbursement for taking care of a sicker patient.

If the physician doesn’t report patient health information fully and accurately, omitting the link between complications and diabetes, RAF scores are set too low and the payer does not have an accurate picture of a patient's health, which results in lower reimbursement.

Risk Adjustment Auditing and Monitoring

Documentation and coding for risk adjustment is complex, and to ensure data accuracy, healthcare organizations should implement regular in-house audits and monitoring of their value-based reimbursement programs. Regularly auditing and monitoring your organization’s coding ensures overall compliance and identifies opportunities to avoid inappropriately capturing an HCC code that could lead to an inflated RAF score. Either establishing a formal process to review value-based encounters or selecting a targeted sample can do this.

HCC Coding

HCC Coding: A Shift in Reimbursement Mindset

CMS first implemented the Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) risk adjustment model in 2004 as the methodology to risk adjust Medicare capitation payments to private health insurance companies offering Medicare Advantage plans. Since then, the HCC model has been refined and its utilization expanded to include the risk adjustment of patients in a variety of value-based reimbursement plans, including ACOs, Direct Contracting (CMS), Comprehensive Primary Care Plus (CPC+), and many others.

HCC coding is essential to a medical group’s financial success. If HCCs are documented correctly, it creates a more complete picture of the complexity of a patients’ health. Additionally, it often leads to appropriately higher reimbursement to cover the costs of treating patients under value-based programs.

HCC Model Structure

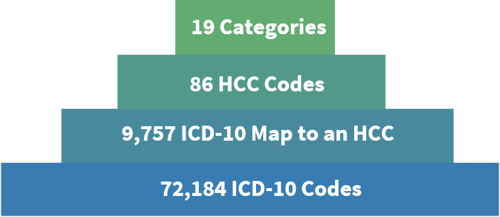

To identify risk adjustment scores and the conditions that predict future healthcare costs, HCC models follow a hierarchy, starting with ailments and conditions documented in the patient’s medical record, which are translated into a specific set of ICD-10 codes. Roughly 13% of these ICD-10 codes that highly correlate to health status and cost are mapped to HCC codes across 19 categories, as demonstrated in the CMS HCC model v24- 2020 below.

ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes

The ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification) classifies every diagnosis a physician notes in a medical record, including symptoms and procedures. The system is based on the International Classification of Diseases published by the World Health Organization.

HCC Codes

9,757 ICD-10 codes map to HCC codes, which represent a specific medical condition. Hierarchies are imposed among related condition categories, mapping them to HCC codes. The HCCs, together with demographic and program information, are used to determine a patient’s risk adjustment score. These RAF scores are then used to predict next year's (prospective risk adjustment) or this year's expenditures.

Condition Categories

Condition categories describe major disease categories, such as diabetes or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The table below illustrates an example of how ICD-10 codes and HCC values are assigned to a specific disease category, diabetes in this case.

| Category | Hierarchy (3 Levels) | Specific HCC Values | Number of ICD-10 Codes Mapped |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | Diabetes 1 | 17 - Diabetes with Acute Complications | 23 ICD-10 Codes (Ex: E11.10) |

| Diabetes | Diabetes 2 | 18 - Diabetes with Chronic Complications | 400 ICD-10 Codes (Ex: E11.21) |

| Diabetes | Diabetes 3 | 19 - Diabetes without Complications | 6 ICD-10 Codes (Ex: E11.9) |

5 Things to Know About HCC Coding

1. More than 9,700 ICD-10 diagnosis codes map to CMS’s 86 HCC codes.

The latter represent categories of chronic and acute health conditions (such as diabetes and congestive heart failure). HCC codes are used to project healthcare costs for patients during current and future coverage periods.

2. HCC coding uses a patient’s historical diagnostic coding history to predict future utilization and risk.

This methodology creates a RAF score for a patient that reflects his or her relative health or sickness. With Medicare Advantage, this score is then multiplied by a base rate to set the PMPM capitated reimbursement for the next period of coverage. Aggregating this across an entire payer-defined population determines the fixed revenue associated with the population.

3. CMS requires that every patient’s record includes documentation by a provider to support the diagnoses.

Providers must therefore thoroughly document each patient’s health conditions at every visit and assign one or more ICD-10 codes to be submitted on any claims.

4. Risk scores and HCCs are assessed annually.

Documentation that supports the presence of a condition and includes the provider’s assessment and/or plan for managing it must be provided at least once each calendar year for CMS to recognize that the patient continues to have that condition.

5. A patient may be assigned multiple HCC codes and certain disease combinations that may elevate the RAF scores.

The specific calculations CMS uses to establish a patient’s RAF score can be complex. However, the primary role of the medical group is to ensure the patient’s record has the complete, accurate, and specific Dx code (ICD-10) that reflects the full picture of the patient’s health. A patient with a poorly documented diagnosis history will always look like a healthy patient to CMS. Accurate coding, supported by robust documentation, will ultimately lead CMS to calculate the correct RAF scores for the patients.

Medical Record Documentation Tips

To support accurate documentation and coding, healthcare organizations should make sure to address the acronym MEAT in the medical record for every patient encounter, which stands for:

- Monitoring the patient’s symptoms and any signs of disease progression or regression

- Evaluating the patient’s response to medication and treatment

- Assessing ordered tests and reviewing patient records

- Treating a patient’s symptoms with medications and therapies

Since every diagnosis reported must be documented with an assessment and plan of care for treatment, documenting the entire MEAT process in the patient’s medical record is important for accurate risk scoring and compliance.

Educating your physicians and coders on best practices will help ensure accurate data and appropriate reimbursement. Essentially there are two important aspects of HCC coding: analyzing the physician’s documentation to identify reportable conditions, and accurately assigning codes to these conditions. Some best practices include ensuring your providers document:

- All cause-and-effect relationships (i.e., linking complications related to a disease or injury)

- All current diagnoses as part of the current medical decision-making process for every visit

- All diagnoses that receive care and management during the encounter, including notes on chronic conditions at every visit if the patient receives treatment and care for the condition

- Only include “history of” or “past medical history (PMH)” diagnoses when they no longer exist and are resolved

Once documentation is complete, organizations should ensure their HCC coding professionals are following the Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting from CMS. The guidelines provide direction for many of the coding issues that risk adjustment coding professionals struggle with. Many progressive organizations use a concurrent review process, where coders review documentation and diagnosis/HCC codes coming out of an EMR to ensure the diagnosis/HCC codes are supported. This process ensures accurate and appropriate HCC codes are included on the initial claim sent to the payer.

For value-based care models to be successful, providers and coding professionals need to focus on what they do best. While providers deliver excellent, quality care supported by thorough documentation, coders have the expertise to map those notes to the proper diagnosis codes by following the CMS guidelines. Doing so not only helps healthcare organizations provide a quality patient experience, but it also ensures the organizations receive proper reimbursement for the care provided.

Healthcare organizations may benefit from solutions that automatically review diagnosis codes coming out of the EMR to ensure correct HCC codes are captured. Technologies such as these enable you to efficiently integrate concurrent HCC coding review into your existing fee-for-service coding review process. Contact us to learn more.

Get the latest updates

Receive insights on value-based care, revenue cycle best practices and more!